Baudrillard in the Space Colony: Looking Back on Total Recall

5 min read

The Hollywood era of Paul Verhoeven’s filmography occupies a special place in every smirking loser’s heart: The movies are dumb and smart in equal measure, and usually very violent. Where Robocop has been canonized as a too-smart-for-its-own-good 80s shoot-em-up and Starship Troopers is hailed as a triumph of filmic irony, however, Total Recall is most often remembered for being “trippy” and for having Arnold Schwarzenegger in it. In this post, however, I would like to take the time to rejuvenate the film’s subversive potential: To the same extent that the film exists as a schlocky piece of power-fantasy cheese, it is in every way a damning takedown of the function of such entertainment in cementing the power of empire.

At a glance: Schwarzenegger’s Douglas Quaid is a construction worker who literally dreams of adventures on his universe’s Mars colony. When he’s not dopily wielding a jackhammer or dreaming about space, he’s having the colonial revolution streamed into his eyeballs by his world’s—and our world’s—omnipresent screens. Eventually, he grows bored of his comfortable life and pays a visit to Rekall Inc., a service that implants memories into one’s brain of anything from a vacation to the beach to a spy adventure on Mars. Unsurprisingly, he chooses the Mars package. During the implant process, however, his secret identity is awakened: His quixotic existence didn’t just seem wrong—it is wrong. He’s not a worker dreaming of being a Martian spy, he’s a Martian spy who’s had false memories of a normal life on Earth injected into his brain. Suddenly everyone in his life is revealed to be a sleeper agent bent on keeping him sedated and he escapes to Mars to complete his mission as a freedom-fighting revolutionary. Throughout the movie, his true identity shifts: He’s not a revolutionary spy, he’s really working for the colonial government. Or is this all part of the spy adventure from Rekall Inc.?

The movie is, of course, too smart to answer that question. At any given moment, it is up to the viewer to decide if Quaid’s reality is real or false. He could be a workaday construction man or a revolutionary hero, a willing administrator of imperialism or a customer receiving a masturbatory power fantasy in which the revolution depends on you. Quaid, for his part, is all too ready to accept that his whole life is a sham. As soon as the opportunity avails itself, he goes out of his way to perform the part of the master killer and adventurer. He’s obviously shocked to discover that his wife is an enemy agent in deep cover, but once he’s done some espionage he is more than happy to shoot her dead: “Considah that a deevorce,” quips Schwarzenegger. While it might seem as if this should prove alienating the viewer, it all works as part of the fantasy. After all, Schwarzenegger makes for a more convincing spy than an everyman. Just look at him.

All in all, the film makes a case that the American male (forget the accent, the movie certainly does) finds his fantasy life more real than his routine: To Quaid, and the viewer, it’s worth killing one’s wife if it means saving the world and getting the (new) girl because the real world is the one that feels better to you, the consumer. By the end of the film, it is equally plausible that Quaid has fulfilled the terms of his artificial vacation as it is that he’s genuinely become a revolutionary hero. We cannot know whether the events of the film constitute revolutionary action because the revolution has been, from the very beginning, televised.

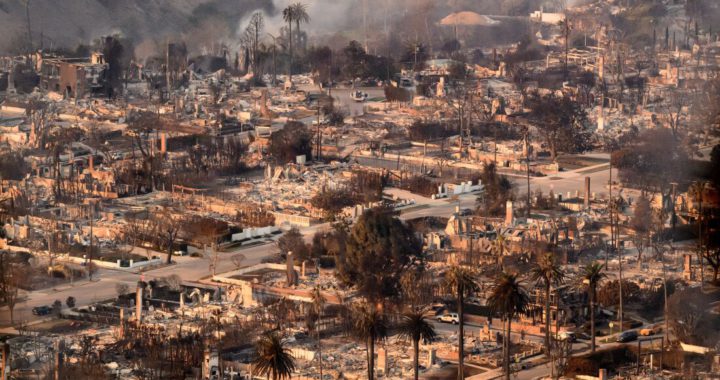

“I just had a terrible thought, what if this is a dream?” asks Quaid at the very end of the picture, before being rebuffed by his love interest and embracing her in a kiss. The film’s Mars colony can never be experienced with any certainty that it is real. It is either a nightmare or a heroic power fantasy, a dream within a dream or a series of distressing clips on the morning news. Verhoeven makes a disturbing case for the idea that, as a beneficiary of empire—how else would a construction worker own that house, after all? —Quaid can’t make contact with true colonial struggle. Because of the film’s framing device, Quaid’s participation in the Martian freedom fight is actually evidence that he is simply enjoying an entertainment product. It strains credulity that the man could experience the exact power fantasy he paid for at Rekall as a coincidence while freeing the Martian people. In the film’s world, the fact that a colonial revolution works out in the favor of a man from the imperial metropole is not evidence of its efficacy, but a suggestion that it’s all a show for his benefit.

Jean Baudrillard hated The Matrix because it offered a simplistic solution to the problem of simulation: In his work, he suggests that mass media has created a simulated reality that does not, by definition, make contact with “the real.” When one is raised in an environment in which reality has always already been packaged and sold to oneself as a media product, the problem of accessing reality is not so simple as “unplugging” from mass media because reality has been absorbed and reconfigured by the media simulation. In contrast, The Matrix contrives a “red pill” that instantly tears away the glossy façade of simulation and gives its team of plucky freedom fighters untrammeled access to reality itself. This is, according to Baudrillard, a cheap treatment of his work. Total Recall, then, could be said to be a postcolonial rendition of The Matrix that more closely hews to the author’s bleak understanding of simulation and unreality. Quaid can never know if he’s truly gained access to revolution because, from birth, his only access to the colony itself was doled out to him as a glossy entertainment product. Even if he were to travel to Mars for real, he would see it through the distorted lens of the terrestrial news. Even if he were to participate in violent revolution, taking up arms with his colonized brothers and sisters, he would have only corny action movies in the style of the Schwarzenegger oeuvre to guide his actions. Thus, his insistence on catch-phrasing is transformed from a cheesy relic of the era from which the film was spawned and into a terrifying calling card of simulation: Quaid could very well take a shuttle to Mars, arm himself, and take part in what he believes to be revolutionary violence, but he would only ever have access to the cheap scripts of American power fantasy.

– Chet Fuck