LA BURNS

7 min read

‘Los Angeles’ is a poorly understood phenomenon, seated squarely on the nexus of dream and reality. Those who experience it to its fullest are not really there at all – their lives become defined by the costly and miraculous fulfillment of a set of cultural expectations, dreams of what ‘life-in-LA’ ought to be like. To live this dream is to divorce oneself from the land that supports it, and to remain blissfully ignorant of the prices paid behind the scenes.

Some facts that Angelenos will be quick to tell you about their (often adopted) home:

- It’s a desert

- It never rains

- It’s always warm

- It’s always sunny

- It’s a progressive paradise

None of these things are factually true, of course. Los Angeles sits in one the world’s five rare Mediterranean climate zones, which experience hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. The annual rainfall is not extreme by North American standards, but its measurement in inches puts it out of the desert category, and its winter arrival is the inverse of the typical summer monsoon pattern that nearby deserts receive. It is not always sunny in LA. June and July are often gloomy and overcast. The nights are chilly even in the height of summer. On the political front, the city is poorly planned, poorly administrated, wasteful of resources in the extreme, severely environmentally degraded, rife with police gangs and police violence, racially disparate, disdainful of the unhoused, and generally uninterested in providing affordable housing on any scale. Some progressive paradise!

This constant dissonance between the dream of ‘life-in-LA’ and the material reality of its streets and neighborhoods is a quintessential part of the experience of living here. When I talk to people who truly experience ‘life-in-LA’ I can’t help but wonder where the hell these people are living. We see the same sights and wait in the same traffic, but I tend to see hell in the very places that they see heaven. One man’s great achievement is another’s foolishness.

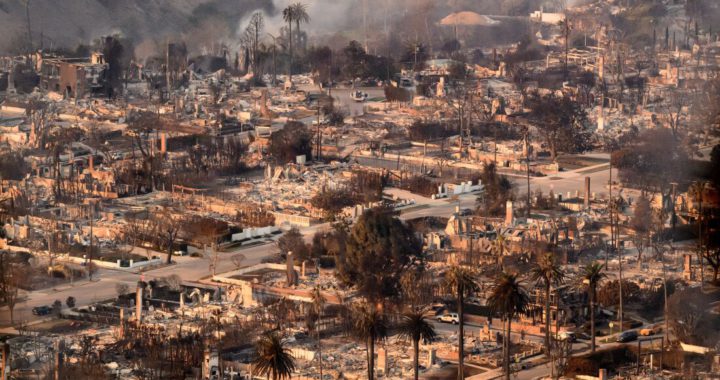

Today LA burns. The Palisades, Malibu, Altadena, La Cañada Flintridge, Santa Monica, Sylmar. I say their names in memory of the homes and lives lost. I hope that we may learn something from the devastation, about ourselves and about this place. About ‘life-in-LA’ and the dangers that bristle under its glossy exterior.

The towns burning today all share one trait: they have been built in areas known as wildland urban interface zones (WUI), which occur most often in the hills and mountains of the Transverse Ranges in Southern California. Here, the sprawl of the city laps up against the remaining pockets of undeveloped wilderness on the peripheries of the built environment. Most of this land is steep, covered in patches of oak woodland and dense, formidable shrubland. The second of those two plant communities is highly characteristic of Mediterranean climates, and known locally to Californians as the chaparral.

The famed Hollywood Hills exist in a WUI, as do Laurel Canyon, Malibu, the Palisades, Beverly Hills. They are grandiose and absurd places to build, signals of wealth and power, too steep to be practical, susceptible to landslides and fire. They are the ideal expression of ‘life-in-LA’ in that they represent a total divorce from the realities and constraints of place. There are those

who would call such absurd and spectacular structures triumphs (man over nature, dreams over reason), and still more who would call them folly.

The Tongva, who inhabited Southern California for thousands of years before it bore that name, largely did not live in modern WUI zones. Indigenous settlements lined the rivers down in the coastal plains of the LA basin. It was flatter there, and carpeted not by thick chaparral, but by the low-lying undulations of the coastal sage scrub, interspersed with shady oak woodland. I am told that the Spaniards who came to California could ride their horses from the northern reaches of Pasadena all the way down the ocean, some 32 miles, and never leave the shade of an oak tree. (Today that same swathe of LA is a long series of treeless urban heat islands.) Few settled in the hills, because in the hills there was little for a human to eat. Grizzlies roamed the shrublands, until they were banished by western colonizers, and pumas. Most importantly – the chaparral in the hills burned.

Much has been made in recent years of indigenous practices of controlled burning. I must dispel any notion here that the Tongva or neighboring peoples regularly burned the chaparral for fire prevention purposes. The indigenous peoples of California generally burned flat areas of sage scrub on the coastal plains. They did not aim to reduce fuel loads, they aimed to eat; many edible species in this ecosystem grow or bloom best in recently burned soil.

The chaparral ecosystem, on the other hand, has historically always burned on its own, and burned ferociously. Fire operated on a long timetable, coming to a given place every 30 to 150 years, but it took no prisoners. Landscapes were burned to the ground, flames fanned by the long dry summers and Santa Ana winds blowing down through the canyons. In such a climate fire was inescapable, and still is. It’s a matter of when. The plants and animals that learned to survive here did so by learning to coexist with fire.

Griffith Park, famous site of the Hollywood sign and eponymous observatory, is also home to a great many acres of protected wildland. Fire consumed 817 acres of it. Teams of scientists were dispatched to see what repair work needed to be done, and the consensus was that, other than some preventative measures for landslides, the land should be left alone to repair itself. It did. Trees and shrubs resprouted from buried stumps. Wildflowers exploded across the newly fertile soil. Jays, hawks, and pumas returned. Today Griffith Park is the best example of healthy chaparral that one is likely to find within the city limits. It’s a cycle that has been repeated time and time again throughout the chaparral’s deep history.

But in the WUI things are not often so convenient. We make sacrifices to live and build in such difficult terrain. In settled areas the fire department enacts brush clearance ordinances, which require the removal of excess flammable plant material from a given property. What counts as

‘brush’ has a strict legal definition on paper, but in practice it tends to be whatever the volunteer fire crew is instructed to put a weed whacker or bulldozer to. This is said to prevent some fire in the short term by reducing ‘fuel loads,’ though the science on such practices is far from settled. What brush clearance does, dependably, is degrade landscapes. It reduces biodiversity. It opens the soil up to invasive grasses and weeds. The soil erodes quickly, and becomes clogged with gopher holes. Hillsides transition from a healthy landscape of interlocking and interdependent parts into something that, to the trained eye, evokes despair. ‘Brush’ has been replaced with a dense tangle of invasive fountain grass, Russian thistle, and mustard, which dry in the summer into light, fine textured kindling.

There is no clear future for this new ‘weedland.’ It is now more susceptible to frequent, low intensity fires, which native wildlife is not equipped to handle. It is susceptible to erosion and landslides. The weeds have not co-evolved with each other to fill distinct ecological niches. They have not fine tuned themselves to this place and its inhabitants. They have little ability to support local wildlife or increase soil fertility over time. What was once a landscape is now a

corpse-like imitation of one. The healthy plant community that once stewarded the land is now gone and cannot return without intensive help.

What can we learn from this? ‘Life-in-LA’ is new, less than two centuries old, and it has made many mistakes. We do not know if it is capable of persisting. The chaparral, however, has persisted for millions of years. It embodies community, biodiversity, and resilience. The chaparral does not hope for an end to fire, it flourishes in its aftermath. Perhaps we can learn from that, but we are people and not plants. We do not resprout. We must instead know our limits as the Tongva did.

Where do we have the right to build? Where do we have the right to live? There’s no obvious answer. The land tries to instruct us on its proper care, but we have ceased to listen. The lessons have become increasingly punitive and severe in response. There is much we should be rethinking in the light of the Eaton and Palisades fires – our role in climate change and rising temperatures, our hubris in attempting to dominate the indomitable chaparral, the floods that could sweep us away now that we have paved and parched the once porous soil, the stretched resources of our fire departments, which Mayor Karen Bass recently cut funding for in favor of increased police resources. Why, in a heating and burning world, would the Mayor have done that? I fear it’s because she is just like us, ignorant, asleep. We who inhabit this dream called Los Angeles have no idea where we really live. Through pain and destruction we may soon be forced to learn.

Resources:

https://californiachaparral.org/

https://friendsofgriffithpark.org/griffith-park-fire-ten-years-later/

-Scapegoat